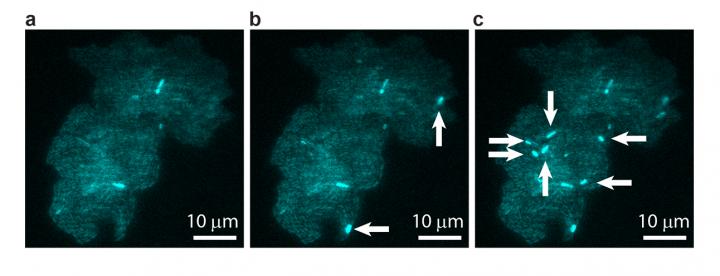

A bacterial colony showing individual cells undergoing transposable element events, resulting in blue fluorescence. "Jumping genes" are ubiquitous. Every domain of life hosts these sequences of DNA that can "jump" from one position to another along a chromosome; in fact, nearly half the human genome is made up of jumping genes. Depending on their specific excision and insertion points, jumping genes can interrupt or trigger gene expression, driving genetic mutation and contributing to cell diversification. Since their discovery in the 1940s, researchers have been able to study the behavior of these jumping genes, generally known as transposons or transposable elements (TE), primarily through indirect methods that infer individual activity from bulk results. However, such techniques are not sensitive enough to determine precisely how or why the transposons jump, and what factors trigger their activity.

Reporting in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, scientists at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have observed jumping gene activity in real time within living cells. The study is the collaborative effort of physics professors Thomas Kuhlman and Nigel Goldenfeld, at the Center for the Physics of Living Cells, a National Science Foundation Physics Frontiers Center.

"In this study, we were able to see that there is actually more of this jumping gene action going on than might have been expected from previous studies," said Kuhlman, whose team performed the in vivo experiments. "What's more, we learned that the rates at which these genes jump depend sensitively on how the cells are growing--if there is food available for the cells to grow, for example. In other words, jumping gene activation isn't entirely random, it's dependent on environmental feedback."

To observe these individual cellular-evolution events in living cells, Kuhlman's team devised a synthetic biological system using the bacterium Escherichia coli. The scientists coupled the expression of fluorescent reporters--genes that encode (in this case, blue and yellow) fluorescent proteins--to the jumping activity of the transposons. The scientists could then visually record the transposon activity using fluorescent microscopy.

"These are genes that hop around and change location within the genome of a cell," said Kuhlman. "We hooked that activity up to a molecular system, such that when they start hopping around, the whole cell fluoresces. In our experiment, cells fluoresced most when they weren't very happy. One school of thought suggests that an increased mutation rate like this might be an advantage in such unhappy conditions, for cells to diversify."

In order to help design the experiment and to calculate what would have happened if the jumping occurred in a purely random fashion, Goldenfeld's team developed computer simulations of the growth of bacterial colonies and predicted what the experimental signal would look like in the random case. These calculations showed that the experiments could not simply be interpreted as random transposon activity and even provided clues as to sources of non-randomness, including environmental feedback and heredity.

"Our work involved a good deal of computational image analysis, followed by statistical analysis," said Goldenfeld. "To extract signals and conclusions from the raw data, simulation and theoretical calculations were integral to the experimental design and interpretation. This sort of collaborative project was really only possible with the unique structure provided by the Center for the Physics of Living Cells."

"The over-arching long-term research goal is a deeper understanding of how evolution works at the molecular level. Direct observation of how genomes in cells restructure themselves allows for a precise determination of adaptation rates and may shed light on a host of important evolutionary questions, ranging from the emergence of life to the spread of cancer, where cells undergo rapid mutations and transformations of their genomes," added Kuhlman.

Kuhlman and Goldenfeld are members of the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology and the Department of Physics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The work involved several graduate students, including lead author Hyuneil Kim, Gloria Lee, Nicholas Sherer and Michael Martini.

Source: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Print Article

Print Article Mail to a Friend

Mail to a Friend